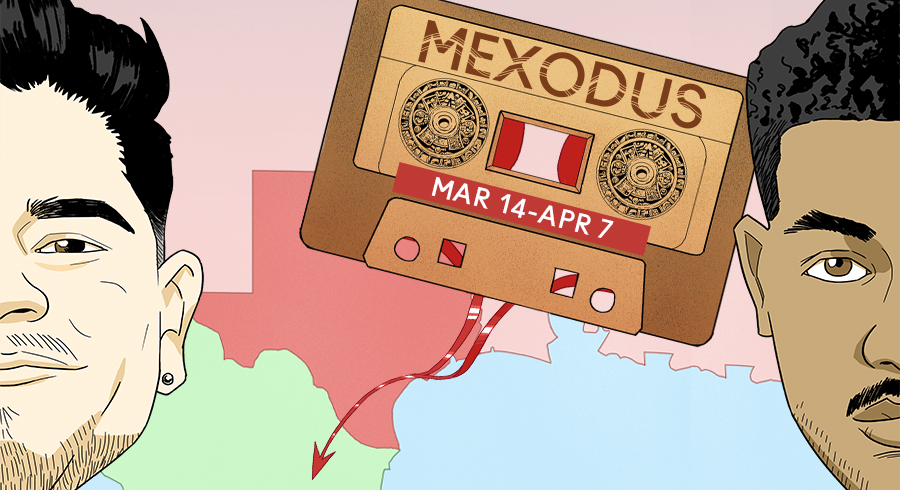

Theatre is forever reinventing itself; telling stories, telling tales and expanding itself. New formats and phases, growing and showing— there’s so many new ways that the theatre keeps going. And this new format of a two-person, live-looping musical telling the story of the Underground Railroad and how it ventured south into Mexico is one of those new innovations. Appearing first at Baltimore Center Stage before it travels over to Mosaic Theatre in DC, Mexodus— a blended hip-hop history musical, a groundbreaking theatrical experience— will give you a story composed in real time that you won’t soon forget. In a TheatreBloom exclusive interview, we have a phone chat with Director David Mendizábal about the story, the experience, and the involvement of bringing Mexodus to life for Baltimore audiences.

David, thank you so much for giving us some of your time to talk about your experience with Mexodus. How did you get yourself involved with this project?

David Mendizábal: I have actually known Brian (co-creator Brian Quijada) socially for a little bit; he was a part of The Sol Project, which is an organization that I’ve been a part of, and we’ve been wanting to work with each other artistically and just had never found the right projects. In 2020, when they (Brian Quijada and co-creator Nygel D. Robinson) were commissioned by New York Stage & Film to begin developing whatever this thing might become and they were making those YouTube videos— that was when I had become somewhat familiar with the work that they were doing, but I hadn’t fully engaged with it until 2021.

That was when Liz Paulson, who’s the artistic director of New York Stage & Film, reached out to me. She let me know, she said, “I don’t know you’ve been following this, but Brian and Nygel— and at that time I didn’t know Nygel— but they have been working on this show. They’ve been doing it entirely remotely and we are giving them two weeks this summer to come together and work on it. Would you be interested?” Originally I wasn’t going to be available for both weeks and then I could do the second week and then they were pleased with that. They thought it was a great structure.

So Brian and Nygel went for a week to New York Stage & Film together. Really in that first week they were like “can we even make this music live? We’ve done this all remotely.” And the idea of it was that we could build it live collaboratively. They got together. They had a draft of the script; Liz had also sent me a draft of the script and she had sent me the videos, so I got to take a look at it. I had never heard of the story of the Underground Railroad that led south, which was the hook. I was shocked; I had no idea.

Then of course, there’s a part me that’s like “I should know this. It makes sense, but it’s not a story that I had been taught in school or anything.” Then when I joined in that second week, it’s also when we invited Mikhail Fiksel, our sound designer, to come in. And that’s really what started our journey. They had been working with the dramaturg, Tlaloc Rivas, who helped them as they were developing and writing the piece. Then I came in as a director in 2021.

They had a week where they sort of played some music and then we got together. They shared with me what they had. I had been somewhat familiar with looping as an idea and I had seen it and appreciated it in music performances. I had not seen it in theatre. There were two rules that they said to me—

- It all has to be performed live.

And when I would ask, “but couldn’t we pre-record—” It was just a hard NO. It all had to be performed live. And then the second one wasn’t so much a rule as it was a question. How do we really interrogate the dramaturgy of looping? And how do we really make the act of live looping as integral to the storytelling as any other aspect of it? That was really what started our journey together and those two things, those two rules remain sort of true for us.

And in that week we just sort of dug into it. They developed the script a bit more. They had 12 songs, one for every month that they had been developing it. That felt important to Brian until we sort of pushed him to be like “what if you break out of this 12-play song cycle and really develop the characters?” We had some really incredible feedback from several artists who were there. There was an artist— Kirya Traber— who was working with HI-ARTS. She invited us to come and develop it at HI-ARTS and that just sort of continued. We would go, we would present, another opportunity would come up, and we’d meet again in a couple of months and then we’d develop it more. Over the last four years, there were so many progressive workshops— and they did some individually, which always happened to line up right after we would come together.

We would come together and if Mikhail was available, we’d bring him. And we would just continue to dig into it and dig into the story and flush out what started as just really beautiful music; it was this song cycle that told a story. We wanted to deepen the story of the characters of Henry and Carlos, but also pull in the story of Brian and Nygel and what is it that they’re trying to say with this piece today. How is this live looping helping us to really bridge the sort of continuum of time between the very present reality of two musicians making music and 1865 with these two characters who we meet and who those two characters become? We wanted to explore the parallels of that journey and the sort of many, many, many years in-between where we have seen these sorts of acts of solidarity and seen them get hidden or buried or rewritten. We needed to interrogate the “why” of that. What are the systems that have prevented us from really embracing the moments of black and brown— specifically— solidarity that have launched entire social movements for change. And figuring out how to bridge that continuum through live looping.

This truly sounds incredible and I’m extremely intrigued. You’ve mentioned live looping a couple of times now and you also mentioned that you hadn’t really seen it before in the theatre space. What do you think this practice of live looping as a stage musical is going to do for theatrical endeavors as a whole? There have been all sorts of groundbreaking features that have come to musical theatre all throughout history; the one that immediately comes to mind is the integration of hip-hop and rap from creators like Lin-Manuel Miranda. Do you think that this format of live-looping is something that may change the face of theatre and what do you think that might look like?

David: There have been shows that have been produced prior to Mexodus that have used looping. There are several artists who are interrogating it in their work. I think we are already beginning to see shifts, especially in musicals. There was this whole fixation around Here Lies Love and the karaoke music in that, right? The way in which music is being created is always changing the form of what musical creation is while remaining true to it in lot of ways. I love musicals. Nygel loves musicals. We are hardcore musical people. So I think with this we are really embracing the musical form while also expanding it to include new concepts and relationships. This is live musicianship. These two artists, these storytellers are also live musicians. And we’ve seen that in musicals. We have seen the actor-musician creating the work, right? I can’t quite predict what this will do, but I think it invites— I hope it invites the possibility of continuing to interrogate the relationship between music and the convention with which it tells a story.

I think that’s often the hard thing with a musical— “why do they bust out into song?” You’re going along, having this deep book thing, but then all of the sudden they bust into song. The song helps them to communicate things when words fail. There’s something about music that allows us to dig deeper, faster into these emotional truths. The act and the art of watching these two brilliantly talented artists actually create the thing— it’s so integral to the storytelling. As I mentioned, it’s a storytelling about solidarity. It’s a storytelling about what happens when we work together to build something bigger than the sum of our parts. And I think that is the interrogation of the live looping for this show in particular.

It doesn’t always have to be the case. I think there are many opportunities in which you can have live looping and it helps to create a sense of this live orchestra, or this bigger orchestra and there’s a myriad of reasons why that might be beneficial from a capitalist point of view. But I think from an artistic point of view, my hope with this is that it continues to introduce and expand the way we think about music in our musicals. That we’re thinking about looping and technology and the way in which modern technology helps us connect to things in the past.

I don’t know what it will do to musicals as a whole, but my hope is that it invites greater possibility. I think artists and writers and creators and musicians are the ones who are constantly helping us to interrogate the sort of status quo of how things are made. You brought up Lin-Manuel, I think there’s something about what he did with both In The Heights and Hamilton which embraced the form of the American Musical and sort of challenged the way we heard it. It demanded that space be made in this very traditional form for new sounds and new cultural rhythms to come in.

I hope with Mexodus that it invites new forms of musicianship and new parallels and invitations to audiences who maybe don’t see themselves in musicals but definitely see themselves in music, to come to the theater.

What is it about this particular narrative— you were saying that it was a point in history that you also were not initially aware of— so what about this narrative really speaks to your creative soul that made you say, “Yes. Absolutely. I need to get involved with this project?”

David: I always say the thing that hooked me into theater was that my father is an immigrant from Ecuador, but came to this country, didn’t speak any English at 15 years old, was a New City cab driver, and ended going to Harvard Law School. Really in a lot ways, he became this sort of American dream. He has his own business now and I would go and I would watch him in court. I would watch him advocating for human rights and for the humanity of his clients. It really made me believe that everyone has a story to be told and the power of being able to tell people’s stories can change lives.

I grew up in Orlando, Florida. My family still lives there. I have a sister who is raising children there and as I look to what’s happening right now in the education system— my mother was a kindergarten teacher, my sister is a teacher— I look to the education system and I sort of joke, “of course I didn’t learn about this {the Underground Railroad going south to Mexico}, I was educated in Florida.” But at the same I’m looking at my niece and nephew and I’m like “Oh my gosh! What are you being taught about history?” This whole war on truth that’s happening is scary. And the idea that there are multiple perspectives to every story but when you’re only telling one that is the dominant narrative or that satisfies the needs of the dominant, oppressive narrative, you’re erasing the complexity of all the actual truth that was going on.

I think literally when I was asked, “Did you know about this?” For me? First of all, I felt kind of stupid. But this lightbulb went off in my mind like “of course, why wouldn’t that be the case where the Underground Railroad went south into Mexico?” When I think back to the work that I have done at The Movement Theater Company, at Sol Project, where I really spent my formative years as an artist, so much of the work that I was building and creating was work with artists of color who were not of my same background. There was solidarity in one of my dear collaborators, Harrison David Rivers, who is a queer black writer, and I, who am a queer Latine artist; we came together and were telling these stories and trying to put our narratives together. I can’t think of a lot of stories in which there is black and brown solidarity on stage. You have your black plays and you have Latine plays and you have your queer plays. There’s this real need in a lot programming to understand “what this is.” What box is it if it’s non-white. Do you know what I mean? It gets one singular box.

Unfortunately I do what you mean; all too often something that doesn’t fit into, what you referred to earlier as the dominate, oppressive, narrative, does get relegated in a label of singularity— “that’s a black play; that’s a queer play; that’s a Latine play.”

David: Right! It’s this sense of “I have to understand where it belongs in order to understand it.” And I have to understand it in opposition to whiteness as opposed to really embracing the sort of intersectional reality of artmaking and storytelling. When you look at the birth hip-hop and how it was black and brown solidarity that came together to create this thing, it was black and brown artists that made it, you’re like “these are moments in time that have happened and get overshadowed.” We don’t want to acknowledge that because there is strength in solidarity and partnership in that intersectional reality of ‘all of our freedom is tied to each other.’ We’re not free until we are all free.

I think it also forces us to reckon with accountability. We’re dealing with that in the rehearsal room right now. There’s this sort of bright, cheery version of “Did you know that the Underground Railroad went south into Mexico?” But then are we also recognizing the fact that there is a lot of complexity in Latin America as it relates to colorism and internalized anti-blackness. How are we reckoning with that? Because this isn’t just some rosy story of “then everyone went to Mexico and life was great.” I think in that act of solidarity it really is asking us all to look inside. What have we been taught that keeps us separate instead of allowing us to reach across those differences?

The show, it’s called Mexodus, and that comes with this sort of biblical undertone of “I am my brother’s keeper.” To acknowledge that and to acknowledge it within communities of color and to say, “yeah, solidarity. Let’s tell more of these stories instead of these stories of division.” So that is really what made me feel like I had to be a part of this. It was something for so many reasons that I had not seen but it’s in sort of the lineage of the values that I think I strive to embody in all of the work that I do.

It’s always so refreshing to hear someone who can speak so passionately and so off-the-cuff but with such sincerity and intensity; I’m truly looking forward to experiencing this project after speaking with you. I don’t know much about this show, other than everything you’ve shared with me thus far and what I’ve read in the press release, but I’m curious to know if there is a moment in the show that defines what this show means for you?

David: We’re still in the process of making it but there are a couple of moments that we’ve discovered, and while we’ve not tried them out— I’m getting that feeling from those. There’s one particular moment, and without giving any spoilers, it’s in the middle of the play. One of the things that we’ve been really interrogating is the porousness between the past and the present. We start with Brian and Nygel, we meet Henry and Carlos, and then we come back to Brian and Nygel at the very end. One of the musicals I continually reference all the time is Passing Strange. I think it just did this sort of meta thing where it was this narrator where we were able to see Stew’s story told but then that moment where they meet in the middle, and all of a sudden the world breaks open and there’s something that just anchors us both in today and in the past— that moment just speaks to me.

We added this moment to Mexodus, this beautiful moment, a sort of fireside story, I’ll say. I just think there’s something about it, I can’t quite say what. It was a lot to introduce because it really broke open a convention but I think what it does is really honor what I believe the loop is doing, which is actually bridging together. Instead of keeping these story lines separate, instead keeping these timelines separate, it is actually showing us the loop that even our own country continues to stay stuck in. It shows us the need for us to really question, “what does it take on an individual level to break free from that?”

I just think there’s that moment, and I don’t want to tease it or spoil it, but in my mind that moment just captures that essence, that spirit so beautifully. It was hard to try to get the writers to want to try this out. But I think it reaches it quite successfully. That moment and just watching these creators be, just watching them make music. One of things that our sound designer encouraged us to think about is world building. The looping is not just the music. It’s also helping us to experience the world of this play. It could easily just be a concert but it’s not. It’s a concert that sneaks up on you and all of a sudden you’re thinking, “I just saw this beautiful play, but it was still a concert.” Finding those moments where that aesthetic vocabulary of words like ‘concert’ meld with storytelling or when you’re able to find the metaphor? It’s amazing. The metaphor of looping is so pronounced in the storytelling that it doesn’t matter that you’re sitting there just playing instruments because I actually understand what these characters are doing in their lives in this moment. I think there’s a couple of moments there where the loop really serves in that ‘world building’ construct and understanding of character relationships in a way that again is like making it a play and not just a concert.

This is going to be thrilling. What is that you’re hoping audiences overall takeaway from this new experience of theatre in seeing Mexodus is going to be? What do you hope they’ll walk away thinking and feeling after having seen the show?

David: First and foremost I hope that they are just excited about theater. I hope that this show creates a great opportunity to bring in new people who have that mentality of “Musicals!? I don’t want to go see a musical!” But then have them leave and say “I just love this great musical that I saw in a theater!”

There’s something fun and sexy about it. I love musicals so much. But it’s hard when we look at all of these movie musicals and they’re being advertised as non-musicals because people don’t like musicals, right? So my hope is that it just really gets people excited, people who are naysayers of musicals that they’re just like, “Holy wow! That was a really dope musical in a really dope story!”

I’m mindful that we’re doing this in an election year. That we’re doing this close to the capital. But I think we’re just trying to make a dope, beautiful piece of theater and tell a really amazing story of solidarity. My hope is that people take that away and just embrace it. Change feels insurmountable sometimes, right? One of my favorite quotes is from the musical Caroline or Change. “Change come fast and change come slow but change come.” I think people get caught up in this idea of “I have to see that change happen immediately.” Sometimes it’s not that though. Sometimes it’s “What can I as an individual do? Nothing.” And sometimes that’s just how it feels, I hope that this show makes people really think about it differently, maybe have thoughts along the lines of, “oh actually I don’t need to do the giant action that’s going create the massive change.” That actually just showing up for their neighbor, just showing up and recognizing another person’s humanity, especially someone who is of a completely different world culture identity/background than me— maybe that— those simple acts of just reaching out, lending a hand, showing up— those little things add up in a big way.

It adds up in the same way the live looping adds up. You add one baseline, then someone else adds another line, you add another and then another and then all of a sudden you have created this massive sonic experience. And maybe you could have done it individually, maybe it would have taken longer, or maybe you don’t have the skill set that the other one does because they are introducing instrumentation that you don’t know, and all of those types of things. But that whole notion of simple actions becoming big change is mirrored in the play. The first number is called “Two Bodies.” We are literally watching two bodies make something bigger than what it feels possible for two bodies to make alone. I hope people take that away with them after they see it.

This this sounds like it’s going to be a fascinating experience regardless of who you are or what place in your life you’re at when you’re attending and I’m thrilled. I cannot wait to experience it. What has your big, personal takeaway for you as a director, as a creative, as a queer Latine individual been from this experience with Mexodus?

David: Two things. One of the things is I’m also costume designing the show. That’s a part of my identity. When I graduated from college, I was doing both directing and sort of fell into costume designing. My grandmother was a seamstress, I grew up around a lot of sewing, I loved clothing and stuff like that and I was doing that a lot. But I was advised to pick a lane and stick in it. If I was a director I needed to really focus on that, which in some ways was good advice because what you pay attention to grows and I needed to really invest in the things that I was wanting to do.

But it implanted in me this idea that in this industry there was not enough room for me to be all the parts of myself. I think as queer person, as a brown person, as someone who is also on their own gender journey, as a director, a designer, a producer— as all of these things I’m never just seen as that one thing. I’m viewed as a Latine director. Or a queer director. Why can’t it just be ‘director?’ It’s that idea that as people of color or as people who have been historically marginalized in this industry, we don’t get to show up in our fullness. So watching Brian and Nygel who are writing and composing and performing and also have to be sound-teching— it’s incredible. The opportunity for this show to introduce two artists living and creating in the fullness of their capacity— it presented this invitation. And at first, I said “No, I’m not going to design it.” But with their support and with the support of Baltimore Center Stage Ken-Matt Martin (interim Artistic Director of Baltimore Center Stage) who was really instrumental in pushing me over edge to do it, I decided I would.

There’s something really profound, I think, for me artistically to get to do this. And there are examples— there’s Julie Taymor and Geoffrey Holder, who have done this. So it is possible. There is room in this industry for us all to be in the fullness of our artistry. And not in every project. I’m not going to go design every project I’m working on because I do love collaboration. But for this one there was something about that possibility and the support that I am feeling both in Baltimore and in Mosaic Theatre (DC) to bring all of myself to it. That’s one big takeaway.

The other big takeaway and it came out at this event that we had at Baltimore Center Stage, this insights event. And actually, I kind of made it up on the spot. But all of the sudden as I was saying it, I realized it was so true— I think as artists of color we’re not allowed to fail. Ever. You have to get it right the first time or else you won’t get another chance. But hooked into the DNA of the show, of live looping is the possibility of failure. If they don’t push the button at the right time and get the chords at the right time, the loop is messed up and then they have redo it. So it’s been this interesting process trying to problem solve, hypothetically speaking, “What happens if we— pardon my French— f**k up?” What happens if we do that? But I think it’s something that we have all been starting to embrace. Because we have built in systems, especially because it’s just the two of them out there on stage. We have built these systems for them to be able to undo and re-record that loop. And because of that, we have built into the DNA of this show the permission for these two artists to fail. And if they do fail, they get to do it again.

When I realized that, it was something that was just so inspiring. It’s scary because you want to do it right, you want to get it right. Obviously we’ll have rehearsal, it will get clearer and it will get tighter. But also they are human and that loop might get triggered wrong or recorded wrong. So you just undo it and then you redo it. And there’s something truly beautiful about that permission— permission to fail and redo— being cooked into how this show is made. Especially for a show that is led and created by artists of color. We don’t get to fail but here— in this show— we do. And if we do, you just do it again, better the next time right? All of that and how it relates to change, how it relates to the story of solidarity, all of that gets wound up in this permission to just keep trying. And I love that about this.

If you had to sum up your experience of working on Mexodus using just one word, which word would you use?

David: Joyous. It has just been a joyful process.

Is there anything else that you wanted to say about the project, about the experience, about why people should come and see it, anything else that we didn’t get a chance to touch on before I let you go?

David: I think it’s really special to have the support from everyone both at Baltimore Center Stage and at Mosaic. At the time, Stephanie Ybarra was the Artistic Director for Center Stage, she programed us, and Reg Douglas (Artistic Director of Mosaic Theatre Company Reginald L. Douglas) at Mosaic, were great. Also this show was produced when two theaters with a black and a brown artistic director at the time said, “We’re gonna come together and we’re gonna do this. We’re gonna figure it out.” And then to have the support of Stevie (current Artistic Director of Center Stage, Stevie Walker-Webb) and this whole team, it’s been wonderful. We have been very fortunate. One thing I think that people have to understand is that we had to start day one in tech essentially with the sound. The first two and a half weeks of rehearsal were painfully slow for me as the director because it was mostly nothing but sound programing. They’re like programming all the stuff into Ableton, which is the application that Mikhail is having them use to program sound in order to make this complex sonic experience.

It is such a blessing for this team to be able to have the gift of time. We are having five weeks of rehearsal at Baltimore Center Stage and the support of the entire staff there, who is just so wonderful and supportive. Mosaic is being supportive too; even though they’re working on their own shows, they’re getting ready for us, they know that this is coming. And to feel that these two companies are coming together? There’s an act of solidarity even in that sort of partnership that feels really beautiful. To be working in that space and to feel supported, to be able to say that this is a grand experiment that when you try to describe it to people it doesn’t fully make sense— and to still have the ‘buy-in’ of these leaders and the support of both of these organizations because they believe in this thing that we’re making and they want to be part of the process, it’s incredible.

I don’t think the fullness of what this show wants to be could have been supported in a traditional process. I think often times when money and resources are so tight, we just fit everything into a sort of traditional structure— like “This is the structure of development.” It feels really important just to uplift the flexibility and the support of the process that we needed to be able to pull off this show— of course, we’re still in it so we’ll see if we can pull it off! But just to be able to realize the fullness of this. That is something special. I think there’s a number of other versions of this project that could have just not reached all of its potential and so it just feels really important to uplift and celebrate the commitment of both BCS and Mosaic to support these artists and all of us as we’re doing this thing.

Mexodus plays March 14th 2024 through April 7th 2024 in the Head Theatre (upstairs; 4th Floor) at Baltimore Center Stage— 700 North Calvert Street in Baltimore, MD. For tickets, please call the box office at 410-332-0033 or purchase them online.