Throw the rulebook right out the window. It won’t help you anyway. And forget what you think you know about Chess as that won’t help you here either. Can’t even say “not your Grandfather’s Chess” because there are so many different variations on this concept album-turned-musical-come-concert-album that it’s hard to pinpoint which one is the one for a standard basis of comparison. Based on an idea by Tim Rice, inspired wholly if not incompletely by historical events. Ish. With music by Benny Andersson and Bjorn Ulvaeus and lyrics by Tim Rice…Chess is the quintessential “DIY” musical because it started life as a concept album. And the Vagabond Players is cracking open their 108th season with somebody’s version of it— Stephen Deininger, to be specific. And the strikingly profound lyric— “Everybody’s playing the game but nobody’s rules are the same, nobody’s on nobody’s side” – have never felt so accurate as they do for this particular production.

If you go into the show with the mindset that it’s a bit like Cats— striking music performed by stellar, local talent, and lots of over-amplified lighting and projection aesthetics— you’ll walk away delighted. (Purists who want whatever stage version they grew up with are probably going to find themselves having less of an endearing experience, though not for a lack of vocal talent on the cast’s part) and for those unfamiliar with the show, it’s an incredibly well-sung concert with thematic undertones of being a stage show.

Director Stephen Deininger, as he states in his notes, is trying to go “back to basics” and go for the concept-effect with this production. What I think he’s achieved is a Concept-Album deconstructed into a musical, which has been reassembled as a concerted and then deconstructed back into a concept, which he’s then reconfigured into a stage-concert-musical-concept. Wrapped in bacon*. The set, also designed by Deininger, is actually pretty barren, save for three large projection screens that dominate each of the walls, and a singular plinth at the center, which holds two chairs and the chessboard table. And all around the stage are the chairs that the ensemble sits in (and the lead players when they’re not standing and singing in the action of the moment.)

Where the conceptual chaos comes into play is with the Lighting and Projections that are used all throughout the performance. Lighting Designer Kaite N. Vaught has some amazing visuals for really intense emotional moments on solo singers, many of which feature high-set spotlights flooding across onto the performers’ faces to create this astonishing illusion that only the person singing is seen in that light. (This happens several times and it never ceased to amaze me because the technique itself seems like something you’d get in a high-quality concert experience and not necessarily something at a community theatre.) Those moments and other clever uses of the lighting are visually striking. But there are definitely other moments where all of the chaos happening with the lights and the motion pulses of ‘light’ captured in the projections on the screens reads almost like light pollution. There are definitely songs where you feel like you’ve fallen down a rabbit hole that’s been enveloped by an old-school Windows screensaver as the projections swirl, morph, distort, and occasionally explode. This is such a jarring juxtaposition to the realistic imagery (and later actual stock footage and imagery) that is used to delineate time and space in the musical. And then there’s the chess pieces, which get projected in motion (think wizard chess but without the people involved) and you get a liberal dose of that thrown into the maelstrom of reality-fantasy-blurry-lines-o-both happening with these projections. It’s disquieting, though I suspect this may be exactly what Deininger was intending; this slightly disorienting, can’t tell what’s real and what’s in someone’s head and what’s a bit of both, all being projected around the cast on the stage as they’re living it, experiencing it, dreaming it, etc.

The way Deininger utilizes the ensemble is also really wild, for a lack of a better word. They never truly leave the stage but they’re not just ‘concert-add-ons’ for their ensemble bits. They watch, they observe, they take sides, they sing. They move (and dance with some impressive routines carefully crafted by choreographer Katie Sheldon) with the frenetic pulse of the show’s drama and the emotional currents of the show’s narrative. It’s really difficult to describe but you could be easily mesmerized and hypnotized just by following different members of the ensemble (at this performance— Andy Belt, Jess Corso, Robert Emmett Dunham IV, Sarah Jacobs, Leslie Jay, Sydney Marks, Miles Weeks) all throughout the journey they’re taking during this musical. There’s live music happening on the stage too (Deininger is seated at the keys whilst singing along and someone seems to find a beat-box to slap on whenever the need for percussion arises.)

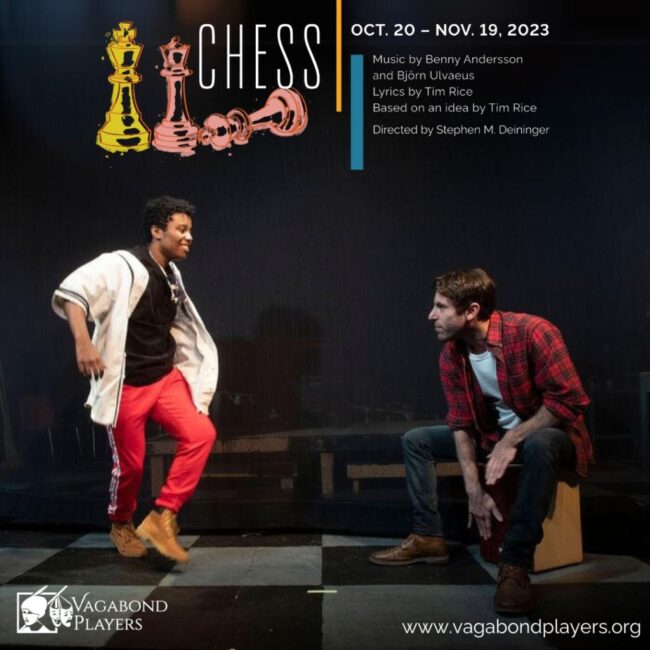

Throw into the mix Costumes designed by Audra M. Mullen and you’ll have a series of questions floating through your mind. Is this a nod to the fact that the musical still has modern resonance or is it reflecting what today thinks the late 70’s and early 80’s looked like? Or is Mullen’s sartorial selection irrespective of time and place and is it just what makes people feel comfortable with that subtle nod to the ear in which the show takes place? There is an amazing wine-velvet frock-coat piece featured on the Florence character that looks incredible, giving the character even more of an edge.

And if all of these dizzying components weren’t enough to upend the carousel and send it careening down the cliffside, there’s definitely some unique arrangements going on underneath these songs. The words may be the same but Deininger has done something, though it’s difficult for me personally to say what because I feel like every time I see a production of Chess I’m seeing a slightly different version (different organization of songs, things cut, things added back in, things removed, etc.) And this version has a whirling dervish of stimulation to draw you in and disorient you; it’s like musical bliss with sensory overload and its easy to lose yourself while watching it. There’s also a very touching tribute to the real-life human beings whose story inspired the show that Deininger projects up onto the screens at the conclusion of the show; it’s pretty striking as well.

The aforementioned ensemble have stellar voices and when they sing together it’s hard to believe there are only (at this performance) 15 of them singing (which includes the seven principal players, who appears to sing in numbers where the ensemble sings if their character is not featured for a solo there.) The music of this show is vastly complex and the score is tricky to say the least, but you’d never know it was community theatre from the sound of it; that part is truly remarkable. “Press Conference” and “One Night in Bangkok” in particular have a great deal of ensemble enthusiasm roaring through them. And somebody (sound consultant Stuart Kazanow likely?) should get a nod of appreciation for that tin-type-microphone effect used on the Freddie character during “One Night in Bangkok”; it’s a fascinating sound.

There are all sorts of moments in this performance that pop, but from a Directorial standpoint the one standing out the most in my mind is the final chess game, Anatoly starts the match against Viigand (Andy Belt) but then steps forward and starts singing/being sung at by the ensemble during “Endgame- Anatoly vs. Viigand.” BUT THE CHESS MATCH KEEPS HAPPENING IN SLOW-MOTION LIVE-TIME BEHIND HIM. With Freddie Trumper making the moves on his behalf. And I feel like this would be an easily dismissible thing, except the way Deininger setup the scene prior— with Freddie and Anatoly talking before leading into “Talking Chess”— this inconsequential background action catches the eye. Did Freddie get into his head? Is this Deininger’s way of showing that the game goes on no matter what state of mind you’re in? Did he let his former opponent sink into his thoughts and guide his moves? It really stands out! And there are little background moments like that happening all throughout the performance, which divides one’s attention, adding to the cacophonic theatrical experience of this production of Chess.

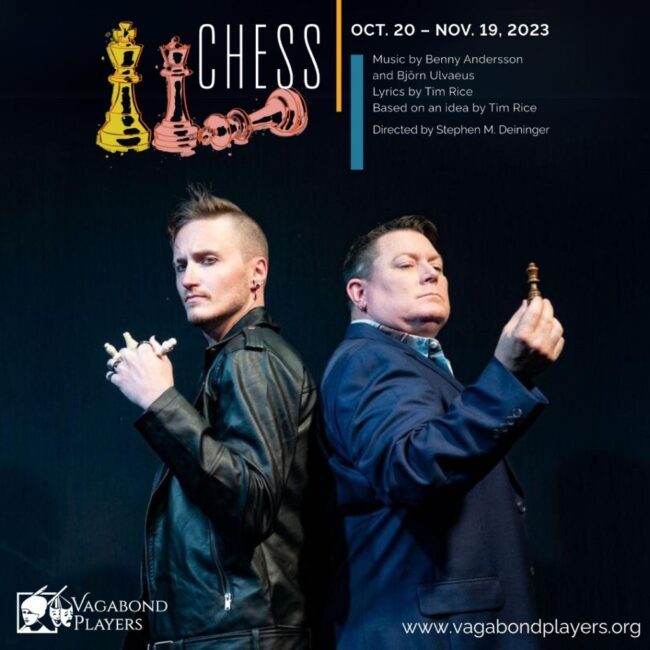

At this performance (due to unforeseen illness) Deininger himself leaps into the role of The Arbiter, a role he’s played before some years prior, and nails it right on the head. The ferocity and intensity with which he attacks his eponymous number is fierce and really lays down the intention behind the character. The clear neutral, as it were. Which is a far cry from the polarizing characters of Water De Courcey (Andrew Worthington) and Alexander Molokov (Anthony Rufo, who is the only person to adapt some kind of vocal affectation/accent for the show). Both Worthington and Rufo have impressive vocal command in addition to solid stage presences. While neither character is particularly savory, both Worthington and Rufo are excellent at gliding them through moments of moral ambiguity, right up until they become ruthless, in which case the pair allow their moral turpitude to reign supreme. Rufo floats through his notes during “Soviet Machine” while Worthington has razor-sharp articulation, particularly during “The Interview.”

Svetlana (Tiffany Dennis) becomes an integral part of the story’s narrative, though not until later in the production. Tiffany Dennis works fluidly as a member of the ensemble until stepping forward as the wife of the defecting Soviet Union Chess-playing champ. And it’s a tall order to stand up vocally against Samantha McEwen Deininger, one that Dennis achieves with vim, vigor, and gusto. The pair share three segments of “duet-aparts”, most notably “Heaven Help My Heart” where they are singing the same song, about the same man, only never truly together in their singing. Deininger’s staging has blurred the lines there as well, which is a unique choice, creating a fascinating dynamic between Svetlana and Florence, who otherwise don’t really interact. Dennis has a beautiful voice that is well-suited for the aforementioned duet-apart as well as “I Know Him So Well.”

With that sensational screaming top-tenor, Jonathan Lighter delivers vocally what anyone familiar with the character of Freddie Trumper might expect. What sets Lightner apart from other Freddies or even from the character as written is the aloof and off-kilter nature that he brings to his portrayal. It’s not wholly egocentric, it’s not wholly narcissistic, but rather this insular bubble. Lightner creates a Freddie that exists inside himself but not in the stereotypical conceited way. You still get hints of that obnoxious self-involvement but it feels more fragile— like a frightened and rejected individual who has turned inside himself because the world outside was too much. It’s a really unique spin on the character that works well in this whirling chaotic dervish that Deininger has created. When you finally get his rendition of “Pity the Child” it feels eerie, rather than the strung-out-emotionally-overcharged ballad that so many others treat the number as. Lightner has an incredible voice and his take on the role is simply fascinating.

Veteran of the musical theatre stage and no stranger to the role, E. Lee Nicol takes up the mantle of Anatoly Sergievsky with a rigid pride and an immoveable sense of duty to the truth of the script, though he balances it with a gentleness that often eludes the character. There’s something to be said for Nicol’s choice to forego the stereotype of a broken half-English-half-Soviet accent and just speak and sing as he naturally does and you find after the initial shock of not hearing it that you don’t miss it one iota. Nicol says a lot for the character with his facial expressions and his body language. And his voice is superb, particularly when navigating the intricate number “Anthem.” Nicol’s articulation is spot on, his sustains are powerful, and his vocal range is vast, servicing numbers like “Where I Want To Be” and “You and I”, a duet shared with Florence, in a striking and beautiful manner.

The way the musical has been presented (at least in the half-dozen other times I’ve seen it— from church basement stages all the way up to the out-of-town-pre-Broadway attempt in DC back in ’18 and a few since) it’s always a story about war— war on the gameboard between the two players, war of relationships where the Florence character is caught in the middle of Anatoly and Freddie, war between nations, the US and The Soviet Union. But the way Stephen Deininger has spun this production around, he’s made the focal point a love story that supersedes the game of chess (though not without the irony that playing the game of love is as strategic, if not more so, than a game of chess) and the focal protagonist becomes Florence Vassy (Samantha McEwen Deininger.) Vocally engaging, Deininger dominates all of the scenes she spends in song. From the jump-off with Freddie, “Commie Newspapers” where you get exacting recitative exchanged between her and Lightner, to her powerhouse explosion during “Nobody’s Side” you get a vast array of talented sounds, emotionally charged musical moments, and all-round frenetic intensity that drives the notion behind this love-story-come-concert. There are a great many opportunities all throughout the performance to experience Deininger’s vocal brilliance; she’s more radiant than the explosive light-projections on the stage and that’s saying something as quite a few of them are day-glow.

Nobody can deny these are difficult times but the decision to get out and see Chess is an easy one. It’s a startling, upending, and jarring new approach to the show, which appears to be wrestling with itself as to whether or not it’s a concept or a concert but it’s refreshing and overflowing with vocal sensations from the local scene.

Running Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes with one intermission

Chess plays through November 19th 2023 at Vagabond Players— located in the heart of Fells Point: 806 S. Broadway in Baltimore, MD. Tickets can be purchased by calling the box office at (410) 563-9135 in advance online.

*There is no bacon.