Unanswerable questions. Unbearable loss. This is the tagline for an evocative new drama presented by Wolf Pack Theatre Company, entitled Masquerade. Written and Directed by company founder and artistic director Bill Leary, the production tackles the tough social issue of suicide, brought to light in the face of a family tragedy. Having the distinguished honor of meeting the playwright prior to the production’s opening, I’ve sat down with Bill for an interview about what motivated him to write the play and what he hopes producing such a production will achieve in the community.

If you could start by introducing yourself to the readers of TheatreBloom and tell us who you are, what you’ve done in the Washington area in the last year or so, and what you’re working on now, we’ll get going.

Bill Leary: I’m Bill Leary and I’m the founder and artistic director of Wolf Pack Theatre Company. I’m also the playwright and director for the current production of Masquerade. Most recently? The last thing I did was A Christmas Carol with the Christian Life Center over in Riverdale. They are a really wonderful church that allowed us to come in and work there. That was the first time I had done anything on stage in quite a while. I had adapted the show and then I ended up acting in it. I played Andrew and the Ghost of Christmas Present. And I know you’re wondering “who’s Andrew?” This is a part of my adaptation, Andrew is Scrooge’s father in the flashback scenes.

What I had done was taken the ghosts and made it so that Christmas Past was Scrooge’s Mom and Christmas Present was Scrooge’s Dad. What I’ve always loved about Christmas Carol is that notion of family ties. You have the nephew and the niece and all that, but nobody ever focused on Scrooge’s family story. So I wanted the audience to see that Scrooge had a back story. That he had a life before he got to where he is now. So I chose to go ahead with keeping the family ties. The Ghost of Christmas Past talks about all of the Christmases that he had as a child. There is a scene that I really love where the Ghost of Christmas Past is talking to him about his sister, who has also passed away. In my version, his sister’s name is Sarah. I wanted this particular scene to be nostalgic and lovely. Scrooge talks about how every Christmas they would have the smells of cookies baking, how they would go into the city to see the lights. Every year his dad, Andrew, would rent a horse-drawn carriage to take them around, and his sister Sarah would pray for snow every year. The two youngest versions of Scrooge and Sarah have this scene where they are spinning around trying to catch snowflakes on their tongue and it really brings in that family basis.

The other thing, that I don’t ever remember seeing with A Christmas Carol, and I know I’m starting to ramble on a bit about that show, but I think it will help you understand where I’m going with Masquerade as far as addressing social issues— but everybody knows the Cratchit family is poor. And beside from the fact that Scrooge doesn’t pay him enough money, they never really talk about that poverty or why they’re poor. With this particular version I’ve taken the Cratchit family and I’ve put them into a homeless shelter. They are so far in debt because of Tiny Tim’s illness; the medications, the doctors, it’s taking a real life situation that thousands of families deal with every day and putting it into a holiday classic to give it relevance.

That was the last thing I did on stage. That was also the first thing I had done as far as directing or adapting in quite a while. I was at an event for our agency, Community Crisis Services, a while before that adaptation and a lot of the kids at the event were checking out McGruff the Crime Dog. I was sitting there realizing that there are all these wonderful things that the agency does and I started wondering. What is that I can do that will— A.) Help the agency, and B.) that will get me to be creative again? For so long I pushed that part of my life off to the side and I missed it. There was nothing that I was doing that had that passion that I had always had. It sounds kind of dramatic but I had felt like a piece of me had died. I wanted to get that part of my life going again and in a way that would help the center.

I knew I really wanted to go back to theatre, it’s always been my first passion. I had talked to Tim Jansen, the executive director of the agency, and that’s how Christmas Carol came about. People were so shocked at the way I transformed the show, it was really wonderful. And that got me going for Masquerade.

Wolf Pack Theatre Company is relatively new as a company, can you tell us a little bit more about it?

Bill: Well part of the mission of Wolf Pack is that a portion of the proceeds from every show goes back into some charity. Like with A Christmas Carol a portion of the proceeds went back to the Community Crisis Services for their Warm Nights Hypothermia program which is a yearly overnight shelter at various churches throughout Prince George’s County, and another part of the proceeds went to the Christian Life Center’s Food Distribution program. So it really was a situation that while the show was mine and I was still doing it, I wanted to make sure that I was still giving back to the community with it because the community has given a lot to me.

Like every artist in the world I’ve made some really stupid choices and I’ve made some really bad decision. I was lucky enough that I had people that I could depend on. When I started the company, I wanted to make sure that the gratitude that I had for the people in my life could help somebody else. The other part of starting this company was to give talent in the area a chance to grow. A lot of the companies in Washington DC have a core group of actors that they work with already. I don’t necessarily want to name companies in particular but they have that core group that they work with and few new emerging creatives, or for people who have been out on the fringes for a little bit longer than we’d like to admit to, it’s very difficult to break into those scenes. There is edgier new work being done, but it tends to be by playwrights that have won a lot of awards or are already well known or are company members of these companies. I want to work in tandem with talent, showing the work of these new playwrights and giving them a chance to be involved; they can be a part of the fundraising and a part of the creative process. It amazes me how many people have jumped at that chance already.

I had a core group of actors that really wanted to do Masquerade, but I didn’t do that. I did have two people who I had worked with before, but that was because they really fit the role. The other four were brand new and three of those four had never been seen in the DC area, this is their DC premier. I really want people to have the chance to show what they can do, and that means giving new people chances. Part of Wolf Pack’s mission is to bring on new emerging playwrights and actors; things that have never been seen in the area.

The company isn’t even officially a year old, but I’m proud of where it is headed. I’ve always been completely obsessed with wolves. Totally and completely obsessed with wolves. And I know that wolves don’t always come with the best connotation they’re ravenous creatures and all, and that did play a part when I was considering the name of the company. I think you have to be ravenous if you’re going to be in this kind of business. You have to be able to go after the things that people may not necessarily find pleasant, the things that people may not necessarily like. But you have to stay true to the type of things you want to pursue. Part of Wolf Pack’s mission is that we are going to focus on social issues, really difficult subjects.

Masquerade, the show that opens this month is about the effects that suicide has on the family after the fact. You never actually see the character that has committed suicide. You hear his voice one time and that’s it. Other than that this is the family within a pastor’s office discussing final arrangements. Every emotion that people would go through at a death by suicide is presented to an extent. The anger, the grief, the blame, the confusion, the frustration, that’s all there.

That’s a perfect segue to finally start talking about this production that you’ve written and directed. Tell us some more about the characters, the story itself, and what this process has been like for you thus far.

Bill: Well I was going to say that the woman I have playing Janet— now Janet is the mother of the deceased man— now hang on, I need to backtrack. When I was writing the show I really wanted Janet to run the gambit. She’s not quite all there, she has these moments where she goes into these little flights of fancy, but she’s the matriarch and in charge. The woman playing her, Lauren Giglio, is a well-known singer and actress in the community. But this is the first time that she has ever tackled a role like this. When I was casting the show, I knew she was the one that I wanted for the role. She fought me for a while, and she kept saying no. But I knew her talent, I knew what she could do and I knew it would set her apart from other actors in the area.

Carol Calhoun, who is playing the grandmother, Emma; she has this stoic, steely, grim determination that is just exceptional. Now, I don’t want to say that I’m just blowing smoke about how wonderful my actors are, but if you don’t believe in your actors, especially for a show like this, you’re not going to get very far. I was actually really concerned when I first wrote the show because there’s this huge amazing amount of talent within the DC area but there were a lot of factors working against me. This is a non-paid show. Hopefully we’ll be able to give the actors a stipend by the end of it but the company is just too new to guarantee them anything other than a portion of ticket sales by the end of the run and that’s after we give the portions of the proceeds designated to those charities away. So that cuts out half of the interested talent right there. Add to that the fact that this show is what some would call “an issues show” that this show very much addresses socially unseemly issues that make people uncomfortable and there goes another half of the talent pool who are interested in auditioning.

I was lucky in the fact that I have six incredible talents that turned up. There’s one pastor, a grandmother, a mother, the father Steven, the biological sister of the deceased, and Kyle, the adopted son of Janet and Steven. He actually feels like he is not a part of the family even though he was adopted as a baby and grew up within the family. Kyle actually has a secret that is directly related to his brother’s death and he therefore very much blames himself for his brother’s death. Through the course of the show that secret is revealed and you find out why he feels that way. It’s a tough situation but the actors have taken this very difficult subject and they have made it human.

I’ve seen the show and I wrote the show so I’ve lived with these characters for over a year. But these six actors have brought so many wonderful things to these individual characters, things that I didn’t see. It’s wonderful to see the humanity brought into these characters that were just characters on a page before. To see what these actors are able to pull out of themselves and put into these characters, and how they all work with one another, I couldn’t have asked for a better cast.

What is it that made you want to write about this particular social issue of suicide? It’s obvious that you are very compassionate and that you want to do a lot for the community. Is there something personal in your life that makes this particular social issue close to home or important for you?

Bill: Years ago when I was a senior in high school my best friend that I had grown up with tried to commit suicide. He put a gun between his eyes, pulled the trigger, and he blew out half of his brain. He lived. Most people who take that step do not live. He now has the mentality of a four-year-old. For years I always wondered why. This was more years ago than I care to admit, but back when this happened this was a situation where the family was asking me all kinds of questions that I couldn’t answer. I was the best friend, therefore I should have seen something, or seen the signs, or understood what was going on. That maybe there was something that he had told me that he hadn’t told them. I had the same reaction to them, surely they had seen something or seen the signs or knew what was happening because I didn’t.

It really became a situation where even though I was in the hospital with him every night for three months, sitting there waiting to see if he was going to live or if he was going to die; his family and I suddenly had a distance between us that we had never had before. A part of that was the unspoken blame. During grief and loss, especially with suicide, people need to blame someone and they can’t blame the person who has killed themselves, so that unspoken blame surfaces to whoever they can deflect it onto, and I think in this case that was me.

There’s a really strong line in the show that deals with that. Steven, the father, says “I can see the blame in my family’s eyes, I wasn’t the one to pull the trigger on my own son.” And he is talking to whatever God that he prays to and he says “Don’t put that on me.” There is this blame and this idea that if someone had seen or known or done something that this could have been prevented. Suicide is unfortunately an issue that leaves so many questions unanswered. There are just questions in these situations that will never be answered and I think my play addresses that; how do you cope and move forward knowing that there are questions that will never be answered?

Each one of the character’s in Masquerade react to Kevin’s suicide differently. There are studies that show for every suicide; it directly, intimately affects six people. Not including those six people, there are an indefinite number of people that are also affected in ways that we don’t even realize or think about. I can give you a great example. During the rehearsal process, one of my actresses found out that a high school friend of hers had hung herself. We were just finishing up Act I at that point. The other six of us in that room had never met this girl, we had never even heard her name before. But because of her death, her suicide, and we care so much about my actress, it affected us quite profoundly. All we wanted to do was protect the young lady in our cast who was going through this.

What has it been like bringing six strangers together to work as a family unit in a play with such difficult subject matter?

My cast is a family. I’ve given them leeway to joke around and have longer conversations than most directors and playwrights would, but they have that bond. The mother and father have worked together before, Lauren and Tim, but none of the rest of the cast knew each other. And it’s fascinating to see the way that these relationships have developed. You know, Lauren and Tim act like a married couple. They bicker, or they’ll joke around and tease each other or pick on each other. But if anybody else says anything negative about them or tries to but in on their inside jokes where they’re picking on each other, they get very defensive of one another.

Sarah and Alie who are playing the siblings, Kyle and Kelly, they will wander off and chat together, you know they go do the brother-sister thing. Kelly Richards, who is playing Pastor Diana, she has a unique involvement in this because she’s not a part of the family directly but she is in the sense that she becomes involved in guiding them through this time of grief and loss. Kelly will sit back and she’ll just watch everybody to see what’s happening with the cast as a whole. She’s the eyes, so to speak, just to see how everyone is getting along. And let’s not forget Carol, who plays Emma the grandmother, she’s become the den mother. She makes sure that everybody is getting enough of a break and she’s constantly chasing after everyone to make sure that we’ve eaten. “Did you get enough to eat? What did you eat today?” And you know, it makes her nuts when we call her grandma, but she’s taken on that role so well and tends to us all, it’s really sweet.

They’ve all fallen into their roles so well without even realizing that they’ve done it. They’ve formed this incredibly strong bond. The subject matter makes this a difficult and emotionally draining show and I think that draws out this amazing compassion from within them. Again, we were in rehearsal when the news broke about Robin Williams’ death, and it affected every single cast member in a very different way. None of us had ever met the man, but we all had this moment. Everybody in the cast bonded over it. They sat around talking about their memories of Robin Williams, which was important. As a Director, you have to let those moments come through, because if they can’t be honest and real in a situation like that or like the young lady in our cast who lost her friend, they aren’t going to be able to convey honest emotions on stage.

One of the things I’ve really worked with them on is to “don’t play anger, don’t play sadness, don’t play those emotions.” You can’t play an emotion. You have to stay present in the moment and focus. Don’t wallow and don’t get mired in the emotions of this particular scene. The audience is going to have the emotions, you as an actor have to stay out of that messy area, don’t sink into it. You have to have that separation of who you are and who your character is. You can go home and cry, but don’t fall apart on the stage. They’ve really taken that to heart and again I can’t say it enough, I couldn’t have asked for a better cast.

The young woman playing the pastor was originally auditioning for the sister role. The pastor was originally written for an older 60-something male. And when she auditioned for Kelly, the sister, I knew she wasn’t quite what I was looking for, but I said to her, “Ok, I’m going to step outside for a minute and clear my mind and when I come back I want you to read the pastor’s monologue.” And I did, and she did, and she blew me away. So I went back in and I changed a few lines, and now there is this incredible woman playing the pastor. The same thing happened with role of Kyle. When I originally wrote the show he was a biological child, not adopted. Ali came into the auditions and he had his monologue prepared— I had sent everyone the script so that they could be emotionally prepared for it. He did the opening monologue for me, and I told him to hang out for a little bit while I saw some other people. He came back in and I had him do the monologue again because I needed to see something. He did it again and when he did it inspired me to rewrite some of the lines in the show. I turned him into the adopted son. I wanted Alie and Kelly in the roles they auditioned for badly enough that it helped me to change the show.

Where does the title Masquerade come from?

The title comes from everybody else’s unwillingness to show their own emotions in a situation like this. It comes from everyone else’s unwillingness to face the facts. Steven, the father character in the show, is very adamant about the fact that he does not want the term “suicide” or the word suicide or any mention of how his son died in the service. His daughter and son are both telling him that this is impossible. Everybody already knows what has happened, not saying it doesn’t change how it happened. All you’re really doing by not saying it is taking a moment that should be able to allow people to connect over this tragedy to understand what’s going on and you’re shoving that into the background. By doing that, the person who committed suicide— their motives, emotions, and actions suddenly don’t matter. Steven is trying to white wash this and you can’t white wash suicide.

At the beginning of the show, everyone hides their feelings. The audience will see the different emotions but the actors themselves until those conversations really get going, they don’t know what they’re feeling or what the others are feeling. That internal battle is very much hidden. Part of the reason I wrote the show was because I wanted to bring an honest conversation about suicide to the forefront. Not just because of my own experience with it, but because at the agency we get so many phone calls from people who either are suicidal or from people who have been affected by a suicide. Suicide is one of those things that just saying the word people are still ashamed of it. If they know someone who killed themselves, they will still try to shove it under the rug because it’s a mark of shame. Too many people have that idea, and that is the wrong idea to have.

After I had written the play and started talking about it on social media— and I was sort of hoping that this would happen, though it ended up happening a bit more vehemently than I was expecting— but people started getting upset at the subject matter. I was accused of trying to make a buck off of a tragedy. I’ve been accused of lacking compassion. I’ve been accused of lying about suicide. There are groups of people who think that suicide happens a certain way. That what they see in the movies— with leaving a letter and crying out for help but people ignoring it— people believe that there is some kind of formula to how suicide happens, and it’s always bundled up neatly with an explanation. We talk a lot at the center about counseling; but not everybody can go to counseling. I’ve been accused of lying about how most suicides happen because so many people have this preconceived idea of how suicide happens. There is no standard answer for suicide.

Look at Robin Williams. He’s somebody who when you looked at him he looked like he had it all: fame, money, fortune, adulation from the public. And then something like his taking his own life happened and people have a hard time understanding that a lot of what goes on inside someone who is suicidal is very internal. That a lot of times you aren’t going to see the signs because there just aren’t signs. There may not be a note.

Has any of this social backlash changed the show at all for you?

I haven’t let that affect the show, but I will tell you that the show has changed, just from where it started when I first started writing it. And I think hearing these things has made me realize how important it was that the show did change. When I first started writing the show, when I first had the idea, the show was written from Kevin’s viewpoint. The writing was horrible. The other characters kept pushing their way in, they wanted— no they needed to tell their story. Which made me realize that it was their story, not Kevin’s. That it was their story about how what Kevin had done affected them. Part of our promotional tagline is “one family’s emotional story of suicide.” And it is their story. It is not Kevin’s story even though it’s based around Kevin’s suicide.

I saw a production a while back called Suicide Inc. In this show the guy who committed suicide was a character, he was a ghost. Too often suicide in a play or a movie gives you the ghost of the person or the person alive in all these flashback scenes. Nobody ever wants to talk about what happens afterward. It gets sticky, emotional, and messy, and nobody wants to deal with that. You know in Masquerade, most of Steven and Janet’s friends would be happy to white wash it and move on. But that’s not how it is. I want my writing to be honest. I don’t want to go into the ghost thing, there is a place for that, but this isn’t that place. When you’re trying to start an actual conversation about a very difficult subject matter you have to base that in reality.

What has the rehearsal process been like for you and this cast?

The cast has been very up front with me about it. There have been times where they have had to walk out of rehearsal. “I need to stop for a minute this is a little too intense.” And they’ll take their five or ten minutes or whatever is needed, walk away and come back. They might all be ready to kill me right now because it’s so dialogue heavy, but that’s a different play, we’ll call it Homicide. It’s just how I wrote it— there seem to be a lot of non sequiturs happening or many conversations going on at once. You and I both know that when you’re at a family dinner you’ve got this person over here talking, this person over there talking, you’re trying to answer three different people, and someone else still asking about something from twenty minutes back; it’s a lot happening at once. I have all of those family dynamics rolling around in those conversations.

The cast, when they’re studying and trying to learn their lines, they’ve gotten to the point where they can relate to their own families. Watching it up on the stage is one of the most incredible things I’ve ever done. It’s scary as all hell. There are moments when I want to run screaming from the rehearsal, and there have definitely been moments where all seven of us have looked at each other and said “What the hell did we do? Why are we doing this again?” But at the end of the day the one really great thing is that every single person is committed. They believe so much in what we’re trying to do with this show, and that all conveys on stage. We get through the rough spots and we’re making something incredible.

What has been the biggest challenge for you as a director with this show?

First and foremost? Finding the people that I felt comfortable with. And then finding the space that I wanted to work in. I was lucky enough that I did get a grant from the Prince George’s County Arts and Humanity Council. They read the script and loved it. I did a kick-starter campaign, and there are enough people out there who loved the work and love me that they put their money up to support this. Finding the Charis Center was a blessing. It has the intimacy for a new theatre company, especially for this show, and it brings the audience directly into the action. It only seats about 125 people. The audience will be able to feel the actors and their emotions a little bit more than if we were in a 1,000 seat proscenium. It’s like a Tennessee Williams’ play, if you see it in a smaller venue you’re able to feel much more connected to the people. At a bigger venue you can enjoy this show, and enjoy what you see, but you don’t get that connection and with this show I really wanted the audience to get that connection.

Will Wolf Pack Theatre Company be a regular company at The Charis Center?

Now, for the next year the Charis Center will be Wolf Pack’s primary home. I was so thrilled when we came to that agreement. We have five shows planned, including A Christmas Carol, although that will be over at St, John’s Lutheran Church. It’s not at the Charis Center for a couple of reasons. This version of A Christmas Carol is set in a church. It’s not Scrooge going home with the door knocker and all that. This is Scrooge coming into a church on Christmas Eve because he feels compelled to come there. This is a very different adaptation; something that nobody until last year had ever seen. I really wanted that show to be set in a church again, it brings that intimacy and realism and I love realism in my shows.

I haven’t made a solid commitment to the upcoming season, but I’ll talk about it anyway. After Christmas Carol I think we’re going to do Nunsense. I know everybody and their brother has done that show, but occasionally you have to have a mainstream show to support all of these other shows that we really want to be doing. I have to consider things financially from time to time; if we want to be able to do the shows that Wolf Pack stands for, we have to do a mainstreamer to bring in the finances to support it.

So unofficially the line-up right now stands as Masquerade, Christmas Carol, Nunsense, and then we’re going to do Forsaken Angels, which is a play I’ve written about human sex trafficking. It’s from the viewpoint of these two women who got involved in sex trafficking, and their memories about their lives involved with that. Then I’ve asked people to send me new scripts— and I’ve got about 16 scripts that I’m reading through to make a selection. And then I was looking at doing a second musical, City of Angels, which is a show that I’ve always wanted to do. I’m hesitant because it’s a really difficult show to do, and the Charis Center might not be the venue for it…so I’m considering Sordid Lives as an alternative. That right now is the unofficial season for Wolf Pack.

I want Wolf Pack to be able to put on a show and do it well. I do not want to do a show just to say I’ve done it. One of the big reasons that I’ve really pulled back on City of Angels because it is such a difficult show, I know that I don’t have the budget or a space all our own, and that is a show that would just be a disaster if I tried to mount it this spring with our current budget. There are just some things that some companies aren’t meant to do, and for Wolf Pack right now we aren’t meant to do that show. We’re meant to look at things like Masquerade and Forsaken Angels and put those sorts of shows out there; strong realistic conversations about real social issues.

What is it that you hope people will take away from seeing Masquerade?

Bill: I hope they will take away the idea that suicide is not as black and white as what people make it out to be. Too many people will look at it and say “he was mentally ill so he killed himself” and that’s the reason. Or they’ll say “oh he was just depressed.” When in actuality there are so many layers and factors that go into someone going from depressed to that point of wanting to end their own life. I’ve never actively sought out ending my own life. I have never had that feeling or emotion, for lack of a better word. But I have made choices that were destructive and could have been viewed as suicidal. The old movie, Looking for Mr. Goodbar, where you’re actively seeking out things that could damage you. I didn’t realize it at the time, and I was lucky enough to have a group of people help me out of that.

But so many people look at suicide as something that an individual makes a conscious decision to do. It isn’t always that. You may be to the point in your life where you feel like everybody else in the world is against you. Or you don’t have anybody to turn to. The one thing I want anyone in that position to feel is that there is help. There always is somebody who cares. You may call the suicide prevention life-line but there is somebody there who will talk to you and who will do what they can to help you. You may never see that person in your life, but for those five minutes, they care. I want the audience to walk away knowing that there is help out there. Sometimes all it takes is time, time to realize that you are not alone and that suicide is not the right choice.

After each performance we are going to have a question and answer period for the audience members who would like to stay. I very much want the audience to drive the questions; I don’t have an agenda or anything like that. I want them to ask us whatever they want. A portion of the show’s proceeds, as I mentioned, are going to suicide prevention and counseling efforts. I hope that this show will start an honest conversation. I don’t want suicide to be something that people can’t talk about or are afraid to talk about. It’s a fact of life. You don’t have to like it. I don’t like spiders. But not talking about them is not going to stop the spiders from existing. Suicide is still going to be in the community whether you talk about it or not. It is part of our every day consciousness. I want people to understand that it is something that is a part of who we are, and that they can talk about it.

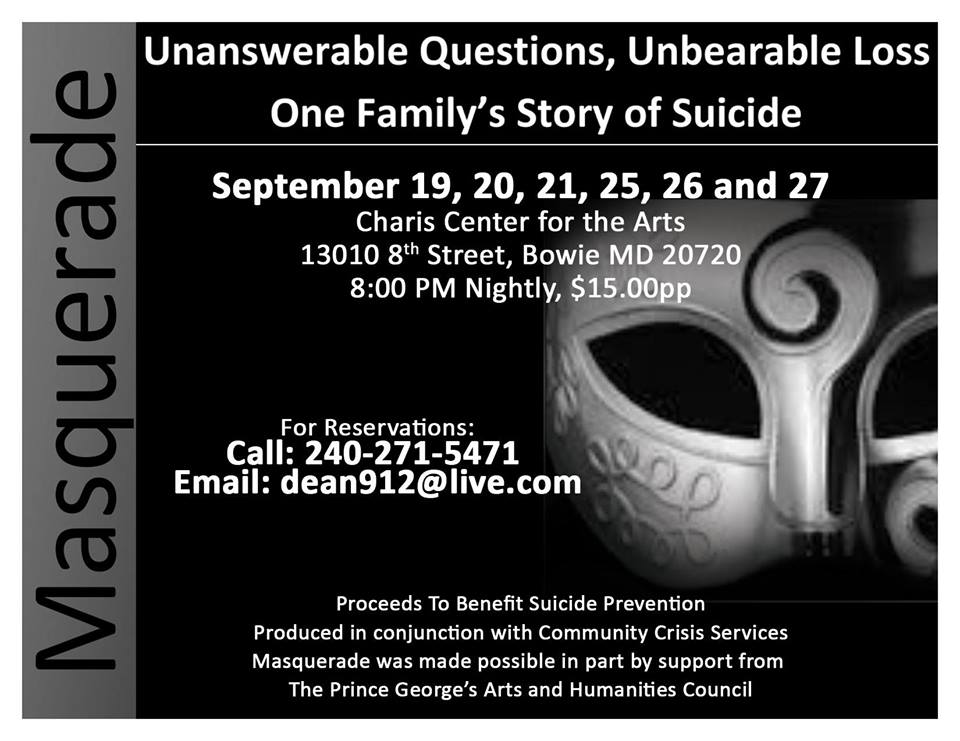

Masquerade plays through September 27, 2014 at the Charis Center for the Arts— 13010 8th Street in Bowie, MD. For tickets call the box office at 240-271-5471 or purchase them online.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, please pick up the phone and call the national suicide prevention lifeline— 1-800-273-8255.