Christmas time is a bright and wondrous holiday season. Often described as the summer of the soul in December, a great deal of classic shows mount the stage during the holiday season but perhaps none so frequent as Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. At this festive time of year in a TheatreBloom exclusive interview, area actor Paul Morella took a moment to sit down with me to discuss his one-man version of the iconic Christmas classic. A truly marvelous interview, Morella outlines why Dickens in its most basic form is truly one of the best ways to experience Christmas this year.

If you would start by introducing yourself to the readers of TheatreBloom, giving us a little list of what you’ve done in the area that they might have seen you do in the last year?

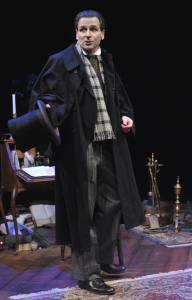

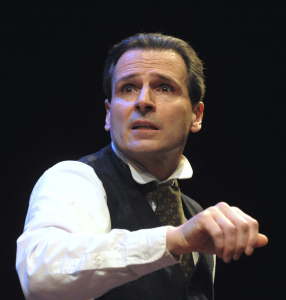

Paul Morella: I’m Paul Morella and I’ve done a number of projects recently out at Olney Theatre Center. I was in Awake and Sing! a few months back, and prior to that, I was in the National Players outdoor production of The Tempest. Earlier in the year, I was in Richard III at The Folger, followed by Underneath the Lintel at MetroStage, It’s nice to branch out with other theatres and get different perspectives and different audiences. I’m always amazed at how the demographics of the audience shifts, depending on the area. I wish there was a way for the theatres to collaborate more, so that separate theatres can be part of a larger theatre community.

That’s a great segue for getting us started in this interview, with everyone being a part of the bigger theatrical community, everyone has something they’re putting on for the holiday season and more often than not it’s some version of A Christmas Carol. What is that saying about the theatre community as a whole?

Paul: With this piece, there’s enough of this sort of Dickensian mince pie to go around. The material can handle many different approaches. It’s not like there is only one way you can experience it. I find it fascinating to see so many different companies present their version on stage every year. It’s just like the way the same play can be experienced in many different ways depending upon the approach or the interpretation or even the performers that are in it. It’s quite a revelation to think that these are the same words, same story line, but suddenly you have a completely different show just because other elements have changed.

You have A Christmas Carol in its purest, most basic form— the text straight from the novella delivered as a one-man show. How did you decide that this was how you wanted to portray this classic and how did it come about to be what it is today?

Paul: Well, I have a one-person Clarence Darrow show. I’ll try to keep this bit short— it’s a long story with an even longer explanation behind it— but back in 1999 or so I had just finished doing Angels in America at Signature Theatre. Jack Marshall had approached me about doing a one-person play called Clarence Darrow by David Rintels. Henry Fonda had done a production of it a number of years ago and I had seen a production of it at Delaware Theatre Company. I was really intrigued with the show and I was really drawn to the character of Darrow so we went into rehearsals. Leslie Neilson was touring with the show and he was contemplating a stop in the DC area so he pulled our rights. Rather than shelf it for the following season— now this was supposed to open at American Century Theatre so it wasn’t really going to make a dent at any audience Leslie Neilson’s tour would have pulled in— Jack and the Director thought “let’s put on our own version, the heck with it.”

We naively thought, sure we can do that. So we work-shopped it and put together our own version. We decided that rather than stick to the convention of a traditional one-man show, we would break the rules. Let’s do things that you don’t do in a one-person show. Let’s have moments where the audience wonders “was that supposed to happen that way?” Where there may not be a transition or a logical linear trajectory let’s make a character deliberately make the leap because they are sort of venturing into a dangerous territory. Darrow seemed to be the perfect vehicle for this because he’s a fascinating person in addition to being heralded as one of the greatest defense attorneys in history. We decided to make direct addresses to the audience, to make summations to the audience as if they were the jurors. We wanted to bring Darrow to the present rather than bring the audience to the past to tell war stories, which is usually what happens in one-person shows.

That experience for me pushed me over the one-man show hurdle. I think the very first time an actor does a one-man show it’s about “hey, look at me working without a net.” It’s sort of considered the Everest for actors. That to me reads “watch me, look at me.” And if that’s what it becomes about then what happens to the piece? What becomes of the piece that you’re representing and why are you then doing the piece if it’s just meant to be a “look at me” spectacle? Once you get beyond that stigma, it really becomes about the material. Why are you approaching a piece— like Christmas Carol— as a one-person show? What can you accomplish in a one-person format that you couldn’t by doing it with a full cast?

Having the Darrow show under my belt really helped formulate A Christmas Carol. I did the Darrow show, I actually did a full run at Olney, I think mostly because one-person shows are inexpensive to produce. But we did the full run on the main stage there and then I took it to Everyman Theatre as part of their “Explore Everyman” series back when they were on Charles Street. Both runs were very, very successful and I think it’s because the words are— for lack of a better way of putting it— the words in that show are for the common man. They’re not meant to be heard by lawyers necessarily, they’re for everyone. Anyway, I did a run of the Darrow show at The Gaithersburg Arts Barn and that’s where I met Jeff Westlake.

He’s the one, after he saw me do Darrow, that broached the idea of coming back to do another one-handed project. He floated the idea of Christmas Carol. At first I thought “you’re crazy, how can you do Christmas Carol with just one person?” To me it just didn’t make sense. It just seemed like a Herculean task to attack a piece like that as one person, I just couldn’t wrap my mind around it. Jeff said, “No, there’s precedent for it. It’s been done before. Dickens himself used to do it, he would do reading tours of the story.” Dickens would trim it down, almost becoming like A Christmas Carol’s greatest hits, and read through highlights of it. The idea being that he would start from the text and play the characters. He was apparently very animated and people loved Dickens reading his own work.

And it just took off from there? Jeff Westlake said let’s go and off you two went to the races with this thing?

Paul: Not exactly. I still wasn’t certain how we were going to approach it. I went into rehearsal. It was just me and whoever I could pull in to watch me because I was producing the thing myself at the time and had virtually no budget. I thought “if you’re going attack a project like this, what’s the one production element you want?” I thought sound would be the most important element. So I started to think of it in terms of one of those radio type dramas. I was looking for a way into the material.

One idea that I had early on was that it’s a technician at a radio station where they’re going to do a Christmas Eve broadcast of A Christmas Carol. But the cast gets snowed out and they don’t make it. So this radio technician has to make the broadcast himself. I was really into the transparency of it, where the audience would see him making all the sound effects and doing all the characters. So they watch the performance even as they experience the performance. But then that seemed a little complicated and a little too precious.

Then I thought of maybe doing it as a grown-up Tiny Tim kind of thing. Where you wouldn’t know it until the end— a usual suspects Keyser Söze kind of thing— but you don’t know until the very end that it’s Tim that’s been telling you the story. That kind of forces you to look back and rethink everything you’ve just experienced because now it’s being refracted through the prisms of Tim’s eyes. That would have created more of an urgency with the material.

Going back and actually reading the original version of it, I thought I knew it. Everyone thinks they’ve read it, everyone has a copy of it somewhere. But I was so overwhelmed by it in ways that I had never imagined before. I didn’t know it. It had either been so long since I’d read it that I’d forgotten or I had just sort of convinced myself that I had fully read the original, but I didn’t know it. It was so powerful and so resonant. It was so much the kind of beauty of literature where it can actually inspire the imagination to take you places you’ve never gone before. I thought “I’d be foolish to let anybody but Dickens do the talking.” This material as it is— it’s perfect. There’s no reason for me to find some cute or clever way in, just go back rather than go forward in terms of stripping away the artifice.

It’s written in the first person narrative. When you hear the words come out of your mouth and off the page they sound very organic. They’re not like a lot of literary adaptations where you can almost hear the pages moving. I thought “There’s really very little I need to do.” Then the precedent of Dickens himself having done it this way, I thought “let’s just do it this way.” That first run back in 2009 was kind of work-shopped that way. I didn’t have a director per say, just a couple of people that would come in and I would bounce things off of them.

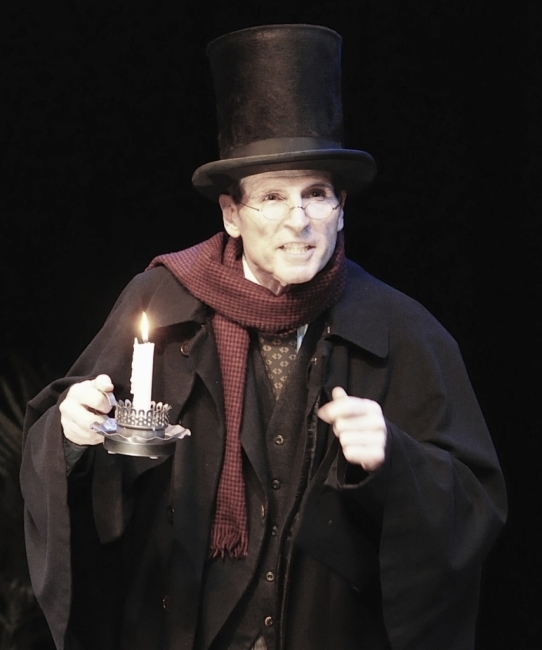

Some of the things that have evolved in the production since then were very sort of serendipitous elements of that first run. I couldn’t afford to hire anybody for front of house that first year. I sort of had to stand at the front of the house and take tickets and usher people to their seats. I was doing it myself. People seemed to really enjoy that. I really enjoyed it, actually. I loved how it contributed to the informality of the storytelling aspect of it. It’s something that I find enjoyable because it immediately puts the audience in the frame of mind that this is going to be a different experience. This is not a theatre presentation in a conventional sense. This is going to be something that is going to be shared and unique. Welcome to my home this holiday season for this ghost story told around a Christmas fire.

You’ve essentially become Charles Dickens, inviting people to the readings in a sense then?

Paul: But I’m not Dickens. That’s not what this is. I’m not Dickens doing this reading, I know people think of it as “that’s the way in,” but I’m really just a Dickensian version of myself. Again, I’m just stripping away the artifice and conversing with them. I love getting to talk to the audience on the way out— again that was sort of born out of necessity from the first time this production happened— and that much like many of the most inspiring moments in theatre all happened by accident. They always happen fortuitously or serendipitously. When you’re forced to deal with just the basics it allows your creativity and your imagination and your willingness to collaborate with your audience to really make a unique experience for them. The goal from the very beginning has always been to have the audience be participants rather than observers, to bring them into it.

You mentioned that this did not actually start at Olney Theatre Center though I know a great deal of your audience has come to recognize it as an Olney Theatre holiday tradition, when did it make its move there?

Paul: It started at the Gaithersburg Arts Barn in 2009. So here in 2014 this is the sixth Christmas I’ve performed the show. It moved to Olney that following Christmas in 2010. This is the fifth year at Olney. It’s also important to know— regardless which venue the show is playing at— that this is 99.99% Dickens words from the original novella verbatim. The only thing that I have added is the carol that Tim sings at the Cratchit dinner.

Dickens did not give a carol in the original version. He says “and then they had a song sung by Tim about a lost girl in the snow and that he sang it in a very plaintive voice.” So I found a song. Usually a production has Tim sing a conventional carol like “The First Noel” or “Silent Night.” There have been a number of theories as to what song Dickens intended but did not give. The only clue he gave was that it was about a lost girl in the snow. Some people think it was based on a Wordsworth poem Lucy Gray. The young girl is sent to go to town to get her father and she dies in the snow on the way. Whenever the family makes the walk through the woods they hear her at night.

It’s one of those haunting poems that is sort of upbeat in the sense that her presence is still alive but still terrible that she died. The idea of Tim singing that song? You can just imagine them all having this good time and then Tim sings that song and everyone is sort of thinking “what the heck, what are you thinking, Tim?” There’s a greater maturity to Tim with that song. He’s usually perceived as the little cherubic poor crippled boy. He’s not. Bob says “God bless us.” Tim says “God bless us everyone.” He elevates Bob’s toast to something even richer and deeper.

That’s another thing that happens throughout. We as adults learn from children. The children in this story have more maturity than the adults. I think that’s fascinating, Dickens’ love and respect for children, not only what we can teach them but what they can teach us is right here within this story. I found this old obscure Victorian Carol, and I’ve had people tell me that they think that this carol was Dickens’ inspiration for Tim’s line “God bless us everyone.” Because that line is in the carol that I use. I found it, I listened to it, and I thought it was perfect for Tim to sing. I think it’s a beautiful way to end that scene for what Scrooge sees and the lesson he takes away from that moment.

How do you keep this show refreshing for yourself, so that you don’t feel like you’re doing the same thing Christmas after Christmas?

Paul: As an actor the beauty of performing is that it’s never the same. It’s not the same year after year not even night after night. There is always that sense of not knowing what’s going to happen once I get out there with this particular group of people on this particular night. It’s a ride that I want to go on and we’ll find out when and how we get there as it goes, but all I know is that it’s exciting.

I know a lot of people look at A Christmas Carol as their holiday cash-cow and they’ll remount the same production over and over specifically for that reason. The difficulty with a piece like this is that sometimes audiences— it’s like going to your favorite restaurant and ordering the same thing— there’s a comfort level in sort of knowing that this is not going to be radically reimagined. But by the same token, I would never want to just remount this thing. This has never been a remount.

It’s a gorgeous wonderful Christmas classic and I understand you have a great number of repeat visitors who have made this a part of their seasonal routine but how are you keeping this show new and engaging for those who do come back? Or is it just that they love what they saw the first time and have to see it again as a part of their holiday tradition?

The beauty of this piece is that it’s had different perspectives take a lot at it and that has definitely helped morph and change the experience over the years. Jim Petosa was my directorial consultant for a few years then Clay Hopper and then I think Martin Platt during his brief little tenure at Olney. And now I have Jason Loewith’s eyes on it. I’ve had all these different people look at it and every year my goal has been “how can I take this apart and put it back together?”

It is reimagining it and looking at it through the perspective of where we are in the now. I have had people say to me how amazed they were at how different it really was this year from the last year. And it really isn’t when you think about it. But it seems that way because you’re different. You’re in a different place than you were before. I’ve actually had people say to me— people who have come early in the run and then return with different people or again by themselves later in the run— and they will say “did you change this or that?” No, honestly! The words are the same; you’re just in a different place and experiencing it differently.

With this being a one-person show, you get to see all the characters through one person’s eyes and that shows you that there are aspects of all of these people in all of us. It does become different show every year— or even during a run with different audiences. Different people experience it differently. It is a shared experience and what they do informs what happens. The lines, yes they’re the same, but how they come out may differ from audience to audience. If they audience is there and they’re more in-tune or want to take the ride in a more humorous vein then we go down that path. If they’re there for the scarier aspects and the more supernatural, hallucinatory elements— I mean it is a ghost story— then we take that route instead.

But how is your version different from everyone else’s version, other than you are one man doing many characters?

Paul: Look at it this way. Here is the most time-honored Christmas story of all time. Everybody has their own version. Everybody dresses it up and puts their own outfit on it. Well my idea was let’s strip it down to the heart, to the pulse of the story. It’s kind of shocking in a way to think that the very first words of this Christmas story are “Marley was dead.” That’s a pretty jarring image. It’s a very, very visceral and strong image. And it’s not even “To begin with Marley was dead” which would soften it if that’s how it were written. It’s “Marley was dead to begin with,” which is an enormously powerful first moment. Dickens doesn’t even get around to saying “Once upon a time on all the days of the year…” until he’s about two or three pages in. You get the initial vision of Scrooge right off the bat. The way he wrote it, even though it has a linearity to it, he brings in all these fascinating literary techniques that really inspire and arouse the imagination and I think that that’s where the heart of this piece is. If you can plant these seeds in the audiences’ mind they will take them to places that you could never take them to. And it will be a different experience when they come back. And it will be different depending on who they bring with them when they come back. People have a vicarious experience when they bring someone else with them.

It’s a different experience for me. That’s the key. It’s an experience not a performance. Particularly with a one-person show if it’s experiential for the performer then the audience becomes a part of that. Dickens even used to say in his preface “I hope that you will have as much pleasure and enjoyment in this experience as I do in performing it.” That was another thing that evolved serendipitously. Doing the pre-show announcement, initially I had no one to do it for me but in doing them myself it completes the experience. Tell them about it, make them feel comfortable and at ease so that if they want to behave in a way that they don’t normally behave in a theatre that it’s ok. Dickens would tell them too, “let it out if you feel so inclined.” I will use that and it contributes to creating this very unique experience that will never again happen this way. The next night it will be completely different.

How is this year’s version different from last year’s version, anything that you’ve brought back or cut out or rearranged, even if we’ll all be experiencing it differently?

Paul: Every year going back to the original text I find myself looking for what I’ve left out that I can put back in. This year’s version runs about two hours with a 10-minute interval and that’s actually where Dickens himself put the interval when he would do the readings. It seems to track just right. If you were to do the full version it’s about three hours long and I think that’s just a little too much. Sometimes he does have these flights of literary fancy and he’ll be very, very descriptive and it just doesn’t translate well onto stage so they get trimmed.

But there are scenes that I would like to get back in there. There’s a beautiful scene near the end— and I’m still looking for ways to possibly work it back in— it’s after Scrooge has seen himself dead in his bedroom. Now in this year’s version Scrooge says “Show me some tenderness…” and they go to Bob Cratchit’s house to experience the death of Tiny Tim. But there is a scene in the original text in-between there where they go to a home of a person who has come home to his wife and kids and you learn that he owed money to Scrooge and it was due that night. He says to his wife because she asks him if it’s good news or bad, and he says to her “Bad…but good.” Because Scrooge has died and that means that their debt will be transferred to someone else and they will have more time to come up with the money.

They’re trying to maintain that somber sense of sadness for Scrooge because he has died, but they are happy. It’s a difficult concept; to find joy in someone’s death the way they do. Dickens talks about the two children that belong to this man and wife watching their parents talk about things they don’t understand and the text says something like “the only emotion the man could show as a result of Scrooge’s death was one of pleasure.” They know they aren’t supposed to be excited because death is a very serious thing, but they can’t help it because this man’s death is good news for them. Nobody wants to have that kind of perspective on things. I’m trying so hard to work this scene back into the current version without upsetting the current balance of things.

It’s really difficult working out what gets cut and what comes back. A couple of years ago I put back in the portly gentleman in the beginning— his scene ends where Scrooge says “If they’d rather die than they had better do it and decrease the surplus population. Good afternoon, gentlemen.” That’s the line that everybody knows. But to read it, what Scrooge says a little beyond that is this “If they’d rather die than they had better do it and decrease the surplus population. Besides, I don’t know that and it’s not my business. Good afternoon, gentlemen.” That gives it a whole different meaning. If you cut it off without that line Scrooge is just bitter and mean. But if you include that line— think about it— how many people do that every day all the time?

The answer is lots. That’s not my business, I’ll look the other way, I have my own troubles to deal with. Whether it’s as simple as not making eye contact with the Salvation Army bell-ringer on the way into the store this time of year. Or ignoring the person who is asking you to make a contribution to whatever it is they are collecting for, and in your mind you’re thinking “no, I can’t I have enough expenses on my plate to deal with this time of year.” And there is a human element to it, just the way we all have elements of Scrooge inside of us. And we may like to forget that we do or pretend that we don’t, but it’s all there.

This year, especially I’m trying to change a little bit of the setting as well, nothing drastic, just enhance the abstraction of it. I mean it is a fever-dream in its own right, the images are pretty horrifying on the page when you think about it, the ideas that occur. Trying to capture that dynamic and the rawness of it, it’s a challenge. This year we’re adding a few more set pieces but they are very abstract. Think like the attic of Dickens’ mind. There’s a grandfather clock added this year, maybe it will be askew, or maybe it exists in the detritus of this world. The idea of this warm cozy Victorian parlor where we’re assembling to hear this tale around a Christmas fire; that’s set in place. But beyond that there is an abstract metaphysical world where stuff has accumulated and piled up, where the carpets end and the fever dream becomes.

You are adding decorative set pieces this year but your props and costumes are remaining minimal?

Paul: I love working with different pieces that can be different things. It happens with the stool a lot in my production. The stool is a stool. It gets inverted and then it’s a goose. It gets turned on its side and it’s a tombstone. It goes back to your early acting class type stuff where you get these few basic props and you’re compelled to create a world out of those few things. If you create it, the audience will go with you. I use a hankie a lot, partly because it gets emotional and I need it, but now I’m looking for ways to make it other parts of the story. It has become over the years the cloth that Mrs. Cratchit uses, then it becomes the table cloth, then it becomes the napkin for Bob around the dinner table. Then it’s the needlework they’re doing when Tim has died. And sometimes it’s just a hankie. But having those things that circulate their way throughout as different things so that the audience envisions them as what they are in those moments, there is great joy in discovering that.

This show requires a lot of the audience. You’re not just coming to let the story wash over you. But people will go there and they will take that journey with you. The description of the Ghost of Christmas Future is so much more harrowing and terrifying if you the audience envisions what he looks like rather than be presented with the traditional/conventional grim reaper image. I get it. I see it. I’m not terrified by it. But to see it through Scrooge’s eyes, and hear the description and then be forced to envision him yourself? That’s 150 different terrifying images across the house. That to me is something that you would never have if you pile on all the effects. You plant the seed and let the audience take it where they will, that’s the real challenge.

It speaks to the personal nature of theatre. The beauty of theatre is that you love for people to think that the show is speaking specifically to them. And it is, but in very different ways. What they see depicted on stage is informed by different experiences they have had in their personal lives. If somebody has lost a loved one— and the way they have responded to that loss— what they see or experience during Tim’s death scene will be very different say from the person in the seat next to them. Everyone sees it different. That’s what makes this show malleable, fluid and constantly able to shift and change.

It’s very apparent that this show holds a special place in your heart. Are there characters that speak more to you than others?

Paul: All of those little bits and pieces that I just mentioned are what make this show so special for me. Fred is always perceived as this Teflon man. Whatever you throw at me I’m going to maintain my merry ne’er-do-well spirit. No matter how mean you are, I’m going to be positive. This is his uncle, Scrooge is his blood. The moment when Fred runs into Bob on the street and Tim has died, I envision this scene playing out so strongly. They’ve only met that once in Scrooge’s office. But when Fred gets the news that Tim has died there is this culpability for Fred on some level because he didn’t do anything. It’s a kind of beautiful moment where Fred’s world order is shaken by Scrooge. He says that he’s going to return every year and invite Scrooge to Christmas dinner no matter what he does, but I do think that it bothers Fred to know that his uncle did nothing to prevent the death of this small child.

It’s moments like that— trying to make the peripheral characters three-dimensional and not just a vehicle, that’s what I live for in this production. It’s looking for ways to flesh them out. That becomes part of the ongoing process for me. What elements scenically or production wise can I work in there to help that? I don’t want to dress the set up too much because the temptation there is to ‘add.’ How can I maintain the simplicity and integrity of the heart and pulse of the story? I say this in my program notes, but I’ll repeat it here— the most potent and powerful sound you can hear in the theatre is the sound of a beating heart. That to me has always stuck with me. The idea that you don’t have to embellish and embroider to get to the heart of the matter. That’s the beauty of storytelling, the beauty of theatre no matter how technical and proficient we become. When you get it down to a human interaction nothing can compete with that. It is so powerful and so direct, it’s the essence of why we were are even here. Communication, sharing, and I think my point in taking the story in that direction and keeping that idea as the through-line makes the piece relevant, resonant and powerful.

You mentioned a ways back there that Scrooge was a money lender, I think like most people I thought he was the mortgage broker in Dickensian era London town. Is he really just a money lender or is there more to that and how did we get so lost in what we think it is Scrooge does?

Paul:That’s really more of a side-note, but yes, he’s a money lender. There is no mention as far as his job goes to what specifically he did other than that he lent money. It doesn’t say specifically what he is ever, I think various productions and versions along the way fill in the details of what he is, but the vague description of money lender does so much for the imagination.

That’s part of the beauty of the original text. Just like the way Fred’s name and Bob Cratchit’s names are not mentioned early on. It dehumanizes them in a certain way, which is the perspective of Scrooge at that time. He says early on when he talks about his clerk— he’s never mentioned as Bob Cratchit by name— only referred to as his (Scrooge’s) clerk, like a thing almost. Fred is the same was as if he doesn’t have a personality. A lot of places feel inclined to drop the names early, a lot of productions will mention them straight away but there was a reason that Dickens didn’t do it that way. It’s only near the end when Scrooge finally says— and it kills me to hear him finally say it, but he finally says “Will you let me in, Fred?” It’s the first time he’s spoken his nephew’s name. That in itself coming from where he’s been to where he is now? That’s enormous.

Working through this piece is like archeology in a way, it’s like analyzing Shakespeare. When you go back and revisit and reinvestigate you discover all these little nuances that you’ve missed and that’s ok, it’s part of the discovery, it’s what keeps me fascinated with it. Recognizing that Dickens wrote this furiously— that he would go for long walks and come back and write, not edit, just write and not revise— to still be able to find all of these incredible things in it— that’s how it stays so fresh for me. You know it’s interesting some of those revisions, because he didn’t start going back and revising until much later and initially he had not included the fact that Tiny Tim lived. It was only after he went back and looked at the galleys and was told that he needed to reassure his readers that he went back and put that in that Tim did live. “And to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father,” that was not in the original. It’s a whole different story without that reassurance.

That’s the beauty of this piece and the beauty of using Dickens’ own words. Let Dickens do the talking, let him take center stage. He’s on a level with Shakespeare, nobody can compete with his level of characterization and imagery and his prose. Dickens didn’t write it as a Christmas story. He wrote it as a story with a social message, the Christmas story just happened to be the way into that message. The oppression of the young, the lack of education, and the whole idea of ignorance and want; that was his message. Scrooge is a very pragmatic business man, he’s not the caricature he’s become over the years. He is you and I; he is everybody in some way or another.

You clearly have a high regard and respect for Dickens and his story, what is it that draws you in so fully?

Paul: It’s everything. I mean everything, like the scene with the death of Tim? Most versions have it where Bob comes into the family and he’s been to the gravesite. What people don’t realize is that Tim is not in the grave yet. He’s upstairs lying in state. Those little lines where Bob goes upstairs and he says “it was decorated cheerfully and hung with Christmas” referring to Tim’s room as if someone had been there recently— hearing that all the sudden you get this image of each of them taking turns going up to sit by his body for a little while. The dignity of the family, the nobility and their ability to survive beyond that struggle is astonishing. They rally around one another and rise above their station despite losing Tim. It’s a killer when Bob talks about the lessons that they can still learn from this first early parting of Tim. He’s not finding a positive in it but it’s how they cope and how they find the dignity and nobility in their station and rise above it.

Just like in the Cratchit family dinner scene. Never a trace of pity or feeling sorry for themselves, they take what they have and they make the most of it. It’s not like “I wish things were better for us” it’s “this is the way they are” and they accept it, they embrace it, and they make the most of it. Those are the lessons that Scrooge learns along the way. Most versions having Scrooge being redeemed at the end because he doesn’t want to die. You have the juxtaposition of the graveyard scene at the end against his reality of waking up in his room and realizing what he’s learned. Scrooge is not redeemed because he doesn’t want to die. He is redeemed because he doesn’t want to die not having lived.

That’s what it’s all about. It’s the legacy, not “oh I fear death.” He fears death not having lived his life. Death isn’t the point, it’s all these things he’s seeing that makes him realize that death is going to come for all of us— and we don’t know how or when— but don’t let it come for you without having lived. He’s not a bad person; he’s just lost his moral compass along the way. The flashbacks to earlier times when he wasn’t like that and what caused him to shift— all of those elements come together and he realizes that he doesn’t want to live leaving behind a legacy where people barter over his stuff and find pleasure that he’s gone. That’s the defining moment, not just being afraid to die.

Do you feel the story is still relative to audiences today, everyone has come to know it as a holiday tradition or a tale at Christmas, do you think the message still relates to today’s audiences?

Paul: It’s amazing how resonate it is to the present day. The juxtaposition of wealth and poverty and all of those elements that he brings in. How many people that we read about and see that are in one of those camps. It’s that time of years as we don’t’ see ourselves as fellow passengers on our way to the grave bound on different journeys— we are together in this journey. It is the one destination we’re all going to arrive at. The one-person show genre— once you’ve cracked the nut of why you’re telling the story— in a case like this one, the why is the urgency of the narrator because the clock is ticking for all of us. It’s not just a whimsical story. There is a message to it. It’s important that we make the most use of the time that we do have not only for ourselves but with the people around us because we are on this journey together and we do know where it’s going to end. I think it’s a beautiful story in that sense.

What has doing this piece meant to you as a performer and personally? You’re very connected to be doing this for the sixth season in a row.

Paul: If it were a piece that I thought had a particular place in time and that it was time to move on from it, I would. If I ever got tired of it or ever viewed it as a remount, or that I was just doing it because it’s work and generates money then it would be time for me to rethink my priorities. The reason that I like to go back to this piece is because it does get taken apart and put back together every year. It is reimagined for me, it is something that pushes me in different directions, and it is something where I learn about myself. I hope that people who see it learn more about themselves by seeing it and learn more about our shared humanity. It does seem to be something that is very unique.

It’s become very special to me. Will it stay at Olney? Who knows. I know there are people who would love to see it done elsewhere just to get it exposed to a different environment. I love that it’s adaptable so if it did go somewhere else it would be unique to that venue and audience. You know even the furnishings from the set— I was scrounging from various theatres to put that together. What are you discarding, what are you throwing out that I can take and put into this set? That’s how this evolved. There was no real design per say, but I like the rawness of that. I think that as an actor each year it grows and moves in a different direction.

It pushes me and challenges me in different ways. It lets me wear all the different hats, not just as an actor. From a production element I get to do it all. How can the sound be altered, augmented, or changed? Sound is very important to me. I wanted a soundscape that would sometimes dictate the action. Sometimes the narrator conjures the sound and other times it appears and pulls the narrator into that world. I wanted it to be ethereal and supernatural and not recognizable. I wanted the audience to hear a sound— in addition to sound effects— that would be a little unsettling but not obtrusive. Not in a way that would call attention to the fact that this is the sound design.

I get to see it from all those different perspectives and it teaches me a great deal and I get to see things through different perspectives which I think is very, very important in every walk of life. It’s not something that’s just trotted out again.

You were saying there is something extra special about this year’s performance?

Paul: This is the first year that it will be performed at another theatre— The Riverside Theatre in Iowa— this adaptation. I’ve been in conversations with them about how this works. I’ve resisted trying to create a “Christmas Carol Kit” where you know, you just open it up, put water on it and poof instant one-man Dickens on stage. It’s been more of a sharing process, where I can walk you through some of these things to help you wrap your mind around it but I’d rather only do that if you have a specific question, otherwise take it and run. This is your project. There’s no right way to do this. Dickens is the star, this is the gospel according to Dickens and if you follow that path I don’t think you can go wrong.

Do you have a passage or a part of the story that really speaks to you or moves you above all else?

Paul: This is one of the reasons why I compare Dickens to Shakespeare. Dickens was in his early 30’s when he wrote this, which is astonishing. He wrote it in six weeks. He had a deadline of Christmas to get it out so it consumed him. What may seem to be at first blush these florid verbal flights of fancy are actually astonishingly well crafted prose for Dickens in that stage of his career. I swear I am going to answer your question here, but that is sort of the foundation of it.

One of the segments that I find to be the most powerful, moving, and compelling is the death of Tim; that second Cratchit scene. Because Dickens has put it where it is, you’ve taken the ride up to that point. Anything that has occurred to you in terms of the physical and emotional toil that’s been taken on you up to that point— your defenses are lowered. By putting it there it’s almost as if the emotional resonance of that scene is so overwhelming that you don’t have to work to summon it. The wave hits and you’re in a very vulnerable position when it does. Just like Scrooge, each event he experiences chips away at that façade at that wall that he’s built up. As the narrator moves through this— by the time that moment is reached, this sort of fragility of the narrator at that point in time— it is very difficult to maintain composure. That’s what the scene is about. Bob is making that same kind of struggle. It’s a revelatory moment because you don’t have to do anything, you actually resist trying to fall apart, but it always hits. And it hits at slightly different points and it is one of those moments where you recognize the beauty of life theatre. You can’t script this. You can’t choreograph this. It happens. And you trust that going in, you trust that you are going to be at that particular place in your world on this journey on this night with this particular audience and the wave is going to hit and you have to deal with it. It becomes that wonderful mix of rehearsed and love spontaneous real genuine existence. It becomes a little bit of a struggle to get back on course but that keeps with the narrative experience that I’m trying to create to begin with. I find that exhilarating. Terrifying and exhilarating at the same time.

It’s like having your favorite spot on the Space Mountain ride. Part of what informs your early experience in the ride is the anticipation of that moment. Even though you think you know how you’re going to respond because you’ve been around that bend so many times, it’s different when you get there. No matter how much you prepare for it it’s going to hit you in a way that you’ve never prepared for or imagined. It’s so alive and so unique and so special and so rare. That’s one of the moments. The whole trajectory of the story— the darkness of the tunnel and the radiance of the light? You appreciate the light much more if you’ve gone through the darkness. It’s like people who are cold and then get warm by a fire— they feel the warmth more than someone who starts out warm with a fireplace in their bedroom. The warmth is the same but it has a completely different dynamic to it. I think people will appreciate the light of the redemption when it comes in this play after going through the darkness for so long.

Is it difficult to draw new audiences when so many other theatre companies are doing their version or somebody’s version of this Dickensian classic at this time of year?

Paul: There are two things that are really important that people should know coming into this show and that is, first of all, that it’s a one person show. And that I don’t read it but I don’t run around putting on all these different hats. How do you articulate exactly what this is when what I just said is essentially what it is and still have people be interested? That’s the struggle, or the challenge, of getting them in the door. Some people think “you’re going to read from the book? What am I paying to see that for?” And then other people think “I don’t want to see some wild crazy guy running around putting on different costumes and hats.” How do you tell them that it’s nothing like that?

The best way I can describe it if I had to do the TVGuide version? It’s a pop-up book come to life. Yes, the words are on the page, but you sprinkle them with your imagination and with your creativity and with this communal aura that we all share as human beings and let’s see what blossoms. That’s going to go in different directions on different nights. It’s telling them that it is one person and that it is a ghost story. It’s not for the very, very young who may be expecting the Disney version.

You know when you go to the doctor that chitchat that the doctor has with you early on? It’s not just chitchat, they’re reading you. They’re analyzing you and looking for clues that are going to inform their diagnosis. By seeing people at the door and talking to them and making the preshow announcement, I get to read them just as they get to read me. I get know my audience that way and understand the dynamic I’m working with before each performance. It’s a two-way street there. Sometimes I’ll say that’s how Dickens intended it and that’s where some people are making the discovery that this is a one-person show. It can be a challenge because sometimes they don’t know that’s what they’re coming into and then they get a little nervous upon making that discovery. But I love it when they go for the ride and the come out and they say “I had no idea it was going to be like this. I was reluctant at first but it was something that was an experience unlike anything they had ever had.”

Seeing people when they leave is not so much giving them the opportunity to chat but to share with me what their experience was. A lot of people ask me “Is that really in there?” This is the real deal. This is the real text. Whatever you’ve heard or seen before, if it’s not this? It’s not A Christmas Carol. They share their personal experiences and stories and I find that giving an audience the chance to share what this experience has meant to them is very much a part of making this theatrical experience complete. This is not your typical theatre event. You see the performance, you applaud for the actors at the end and what you have to say doesn’t really matter— this is not that. What you have to say or think at the end of this experience does matter. That’s the key to it. I get to experience them giving back what this may or may not have been for them. That to me is a very, very important part of it. The evening does not begin and end with the piece itself. It carries out beyond when the lights go out and starts before the lights come up.

I feel like you’ve brought this up the entire time we’ve been chatting, but I have to ask it officially— everyone does their version or some version of A Christmas Carol this time of year. They dress it up or reinvent it and do all sorts of crazy things to it. So knowing that there are all these opportunities out there across various areas of the Baltimore and Washington metropolitan area and everywhere in-between, why should people come and see your production of it?

Paul: I used to say half-jokingly that this was the anti-Ford’s Theatre version. And I didn’t mean that in a negative way, they’re just on opposite ends of the spectrum. I think the beauty of this piece is that it can take that. These two performances are polar opposites but they are both valid in their own way. I know that some people prefer different things. My feeling is that an experience like this one here at Olney, is an experience that you can never get anywhere else.

As an audience member you contribute to what that experience is. You don’t have it laid out in front you, you don’t have the work done for you, you have to fill in the blanks yourself. But that’s not to say that it puts the burden entirely on your shoulders. I think this is something that allows your imagination and your own personal sensibilities to contribute to your overall experience. That’s a kind of a journey that is going to be unlike any kind you can take. It’s going to be unique, and personal, it’s going to be special specifically to you and it’s going to take you to places that you never would have gone to had it been laid out and mapped out for you. It makes audience members more a part of the experience as opposed to merely observing the experience.

A lot of people look at the holidays and know that they have to make their yearly Christmas Carol they have to do it in some way, shape, or form. Whether it’s the film, or on TV, in the theatre, whatever it is, people will need to have that experience to feel like their holiday is complete. And my feeling is don’t go bigger, go smaller. Go to the heart of the story. What makes this version unique is that it is the original. It shouldn’t have to be that way— it should be the rule not the exception. The fact that the original is the exception is telling in terms of our desire for the stimuli. But I think that we get numbed to that. That’s not to take anything away from any of those other productions out there. For me, why bother spending a lot of time and energy and talent and resources on looking for a clever, cute, precious way in when the beauty of the piece is right there in front of you? Just let the story be told in the simplest, purest, most direct and emotionally powerful resonate fashion.

It’s the ultimate experience of reading a book where the characters come to life in your mind. You get to envision what these characters look like, you get to fill in the blanks and it empowers you as an audience member. That is something that is so important in live theatre because people do come in with the equipment that they need in their minds and their hearts and their intellect. The tendency is to overwhelm them, dumb them down and spoon feed them but everything the audience needs is right there. It may be a little difficult to get them started but once you get them going there’s going to be no place more fascinating and vibrant and limitless than that imagination with their own personal creativity. The goal is to tap into that, expose it, open it up and let it run rampant.

I never imagined six years later that I’d be sitting here in an interview talking about how this thing is not only still having life, but how it is still continuing to grow. It’s growing for audiences and it’s still a learning experience for me. People sometimes don’t realize that with a one-person show, when you don’t have other characters to talk with, the audience becomes a character and you talk with them. Human nature being what it is we need to connect with people. The audience is the only other human beings in that theatre. So it really isn’t a one person show, it’s opened up. And I think that’s fascinating. You never know what you’re going to get, and I can’t control that and I don’t want to. That’s not my job. That’s not my goal.

This really is a ride. It’s a ghost tour. It’s a ride that we all go on that has twists and turns, peaks and valleys. It comes back into the station at the end but we are in a different place at that point than where we were when we started. I take the ride and if the audience takes the ride with me then I feel like the show has achieved its goal. Different things are going to happen for different people at different times and that’s the beauty of it.

It’s something that I’m very passionate about and that I truly love doing. I’ll admit sometimes it’s tough, you get tired or you get stuck, and it can be exhausting. And yes it takes away from the holidays in some elements because I’m spending my holidays on stage? But I get 30 Christmases. I get 30 Christmases with 30 different families. To me it’s the kind of thing you can do year round, it is a Christmas story but the message is a year-round message. It would be a powerful experience no matter when it was put on. You don’t have to celebrate Christmas to get the message; this is just the time of year where those contrasts of want and need are so greatly felt. The beauty of this is that whether you’re religious or secular it has meaning. It’s a story for everyone. It’s an experience for everyone.